|

|

|

Chasing

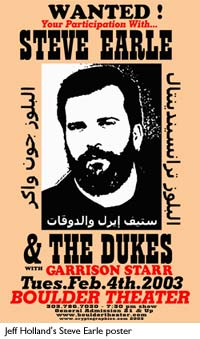

the horny toad back Holland is addicted to live music, too. But with his habit he does more in a day than most people do in 10 years. In addition to designing and hand-pulling screen prints for the best shows that come our way, Holland is a radio DJ, and an archival collector/taper of live shows. He has combined his multi-faceted approach to music appreciation with a very unique gallery show, "RECENTWERKS," now on display at Boulder’s Mercury Framing through Feb. 14. The posters have all been selected from Holland’s personal collection and the gallery soundtrack is made up entirely of unreleased, live recordings taped by Holland during the shows that correspond to many of the posters. Despite the indelible mark he has made on the Colorado music scene, Holland remains a low-profile figure. Despite the fact that collectors the world over buy his posters on e-bay, he is content to use his posters as a means to meet his musical heroes for a handshake, a signature or two, and occasionally the ultimate reward: permission to preserve the show on Digital Audio Tape for "the archive." His archive is extensive–his home is a museum of sound and image. On top of that, his head is a musicologist’s encyclopedia and a graphic designer’s playground. Many people have caught on, recognizing that Holland is not only a viable artist with a massive body of handmade work but also a manufacturer of historic artifacts and a barometer for popular culture. He recently sold a 1994 Dave Matthews Band poster for $376 on e-bay. "I felt guilty about that one," says Holland, humbly. "But if somebody was willing to spend that kind of money, I was willing to help them." He is totally unaware of the value of his work–far too busy being totally committed to a profound, deeply rooted conviction that music is the center of existence. That conviction has led him to design posters for artists ranging from Stereolab and Pavement to Wilco and Steve Earle. He has anticipated the explosion of groups such as Gomez, and championed overlooked greats such as Sparklehorse. "RECENTWERKS," of course, focuses on Holland’s recent works. Last year he made poster history with the wildly original concept behind the Dick Dale/Mermen split. The poster was a single design split between two different shows that were separated by more than a month, but united by one theme: surf music. Both shows also featured Denver’s Maraca 5-0 as an opener. To achieve his effect, the poster was cut in half and each half was distributed a month apart. Only a few astute collectors caught on and managed to piece together a set. One of the uncut originals is featured at the show. Holland’s most recent work is also on display. Done as an old west "WANTED" sign, it features a mug shot-style photo of folk hero Steve Earle. Surrounding the image are the words "John Walker’s Blues," written in Arabic. Late last year, Earle made waves with the release of his perspective-shifting song about the young American boy caught up in the furor of al Qaeda. Like the song, Holland’s poster raises questions about the current political climate in America and hints at the eerie potential for a new phase of McCarthy-style witch hunting. But most importantly, the poster invites Colorado to participate with Steve Earle at the Boulder Theater on Feb. 4 (see article, page 17). As the Earle piece exhibits, the posters are always subservient to his one true love: music. The romance started around age 8. "I used to stay up late with a transistor radio hidden under my pillow so my folks wouldn’t catch me," says Holland, who to hear reminisce about music is to hear a story full of poignant events. In 1969 at the age of 13, Holland saw Hendrix live. In 1971, he saw Neil Young and later traveled to Boston where he picked up a "white-label" recording of the show he had attended. Something clicked. By 1973, he was packing his own portable four-inch reel to reel. Today, Holland carries a DAT machine with him everywhere. It serves him well. He has the ability to snake a line into a soundboard with a deftness that would boggle the mind of a seasoned lock-pick. But he’s an ethical taper who always gets permission from the artist (sometimes after the show). Artists are usually happy to oblige once they realize that he’s neither a trader nor a seller, but a disciple dedicated to the task of preservation–a modern day Allen Lomax. Some performers even look forward to Holland’s stage-side visits. The members of Calexico fall into this category–they look for him whenever they come through town. He’s a hard character to miss. A grizzled prospector with a quick smile in his eye and a Gandalfian beard, Holland waits patiently until the crowds dwindle and then approaches bearing gifts: a roll of his latest poster design and a cleaned up recording of last year’s show. At this point, security is engaged in the arduous task of fan wrangling, but Holland is granted immunity and remains stage-side. This is understandable. He prints posters mostly as an act of homage for the artists he respects. The artists recognize his sincerity and show gratitude in return. Holland’s 1996 Whiskeytown poster made such an impression on Ryan Adams that when he passed through town in 2001, he invited Holland backstage and returned the favor by whipping up an impromptu poster design for Holland’s show on Radio 1190. Mr. Adams spent 20 minutes with a sharpie drawing a full vision of the road on the backside of a poster Holland had asked him to sign. Some musicians are artists, just as some artists are also musicians. On April 6, 1994, Holland was working on a poster for an upcoming Melvins show when the news reached him that Kurt Cobain had died. He grabbed an old screen, blocked out some type and threw it in an emulsion bath. That night he added a memorial in backwards letters at the bottom of the poster. It read: "Kurt lives in our dreams." Melvin’s drummer Dale Grover (who had played with Nirvana) noticed it and told Holland he appreciated the tribute but wondered how he had been able to work it into the poster so fast. For the answer, all one need do is look at another of Holland’s posters–the manic, three-eyed figure staring into the crystal ball from The Flaming Lips show (circa 2000). Like that active figure, Holland is fueled by frenetic energy, only he channels it all into his passion for music and the art he creates to memorialize it. |

![]()

January 30, 2003 Boulder Weekly.

back

If you’re

addicted to live music in Colorado, chances are you’ve followed

the little horny toad to more than one concert. Perhaps you didn’t

notice the toad leading you but it was there. The toad is the cryptic

symbol for Cryptographics and it adorns every poster and flyer designed

by Colorado’s Jeff Holland.

If you’re

addicted to live music in Colorado, chances are you’ve followed

the little horny toad to more than one concert. Perhaps you didn’t

notice the toad leading you but it was there. The toad is the cryptic

symbol for Cryptographics and it adorns every poster and flyer designed

by Colorado’s Jeff Holland.